Key Findings

In many ways, the 2017 tax law (the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, abbreviated as the TCJA) is easy to dismiss as another partisan marker in a radically polarized electorate. The law passed on a straight party-line vote. It is the sole legislative achievement of the Trump administration and was a major policy focus during the president’s first year in office. Poll after poll shows that the law catalyzes deep partisan reactions: strong Republican support and equally strong Democratic disdain.(1)

But a closer look at voter reactions tells a more nuanced story. Data from the bipartisan 2018 VOTER Survey (Views of the Electorate Research Survey) reveals important details on how voters think about this law and taxation overall. The Republican approach to tax policy is generally unpopular. Moreover, most voters don’t believe that tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations drive economic growth and should therefore be prioritized, as they were in the 2017 law. Democratic voters almost universally reject this G.O.P. view of tax policy, and even G.O.P. voters are split.

What does the public actually want from its political leadership on tax policy and the economy? Did the 2017 law deliver? What does public opinion on taxation and the economy suggest about future policy agendas? Data from the 2018 VOTER Survey can help answer these questions. In short, where the public is reasonably clear about what it wants from taxes, it is unconvinced or even skeptical that the TCJA will deliver on those priorities.(ii)

The public’s doubts about the tax law are affecting real-world politics. President Trump continues to celebrate “unleash[ing] an economic miracle by signing the biggest tax cuts and reforms…the biggest in American history,”(iii) but throughout the 2018 election cycle, markedly few Republican political candidates have made tax cuts central to their campaigns. Early in 2018, candidates experimented with running on the tax law. But today, despite the legislative victory of the tax law and strong gross domestic product and unemployment numbers, it seems clear that Republicans on the trail are not talking about taxes.(2) In September 2018, House Republicans passed H.R. 6760, which makes the TCJA’s individual rate cuts permanent.(iv) The 2018 VOTER Survey data tell us that the proposal’s disproportionate benefits for the wealthy and its deficit increases are not what the voting public wants or would prioritize. This again suggests that conservative politicians are out of touch with their own voters.

(1) Vanessa Williamson notes: “Looking at the survey data, this is what we find: an enormous partisan gap in attitudes toward the tax bill. On average, 10 percent of Democrats supported the tax bill, while 72 percent of Republicans did.” See Vanessa Williamson, “The ‘Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’ and the 2018 midterms,” Report, The Brookings Institution, August 27, 2018. Available at:https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-and-the-2018-midterms-examining-the-potential-electoral-impact/.

(2) "'If they can't run on tax cuts in a district Trump won by 20 [points] and win, where can they run on tax cuts and win?’ said David Wasserman, House editor of the nonpartisan Cook Political Report.” See Sahil Kapur, “Republicans Struggle to Make Tax Cuts a Winning Issue,” Bloomberg News, April 16, 2018. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-04-16/republicans-struggle-tomake-tax-cuts-a-winning-election-issue.

For Democrats, the politics of taxation are at least as interesting. For decades, mainstream Democratic lawmakers have been, at best, inconsistent on taxes. Some Democrats have been willing to advocate for higher taxes for the wealthy. But most have been otherwise guarded, rarely making full-throated arguments about the role of taxes in a healthy economy. This reticence can be traced to at least the mid-1970s, when the success and popularity of California’s Proposition 13(3) set off a wave of ballot initiative-driven tax cutting efforts nationwide. Today Democrats, as a whole, are wary of taxation.

But voters want more from our tax system, and from tax reform, than leaders in either party seem to understand.(v) 2018 VOTER Survey data suggest that tax-cutting Republicans should proceed with caution, and that Democrats may have more flexibility on tax policy, and therefore on public investments and spending, than they might think.

(3) California voters approved Proposition 13, or the People’s Initiative to Limit Property Taxation, in 1978. The Proposition is controversial in a number of ways, and focused on property taxation rather than corporate or income taxes. In the early 1990s this amendment to the California state constitution was tested and declared constitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court. See Isaac William Martin, “The Permanent Tax Revolt: How the Property Tax Transformed American Politics,” Stanford University Press, 2008, Print.

The 2017 law is a classic example of the conservative approach to taxation: Reduce corporate and top individual rates to incentivize business investment and economic growth. The law’s central feature is a permanent cut in the corporate tax rate, from 35 percent to 21 percent — the largest such cut in history, accompanied by a one-time overseas corporate tax repatriation provision. The law also lowered individual rates across the board, including for upper-income earners, with provisions for individuals set to expire in five years.(vi) TCJA supporters have said that the cut in corporate rates will encourage companies to invest capital in the U.S., and thus serve as an engine of growth. Its critics have decried it as a giveaway to the rich, likely to worsen income and wealth inequality in the U.S. and designed to satisfy the Republican Party’s corporate donors.(vii)

But what do voters really want from our tax system? Contrary to a one-size-fits-all “low taxes” mantra, Americans’ views are evolving. For decades, surveys have shown that voters cite a range of reasons for wanting tax reform. They believe the system is “unfair” (though the specific sources of that unfairness range and are not entirely clear). A strong majority of voters say that our tax system is overly complicated given the many different deductions and tax credits. That said, tax reform by itself is rarely, if ever, a top priority. Importantly, and slightly inconsistent with beliefs about the unfairness of the system as a whole, most Americans say that the amount they pay in taxes is fair.(4)

(4) For example, in April 2017, 61 percent of Americans reported that the amount they paid in taxes is fair. See Karlyn Bowman, Eleanor O’Neil, and Heather Sims, “AEI Public Opinion Study: Public opinion on taxes,” American Enterprise Institute, April 2017. Available at: http://www.aei.org/publication/aei-public-opinion-study-public-opinion-on-taxes/.

Given both this range of views on taxation, and also increasingly intractable partisan responses on virtually every policy issue, perhaps it is not surprising that the TCJA has never won widespread public support. Vanessa Williamson of Brookings writes that “the legislation was remarkable for its unpopularity; approximately 32 percent of Americans supported the legislation in the lead-up to its passage, a level of approval lower than that received by a number of major federal tax increases in years past.”(viii) American Enterprise Institute Scholar Karlyn Bowman agrees that the law is unpopular, also noting that the public doesn’t closely follow the details of the tax debate. She points out that most media headlines have exaggerated the law’s unpopularity as well as a temporary increase in the law’s popularity in early 2018 — but, overall, her read of the data shows that the public disapproves of the law.(ix)

Finally, the track record on tax polling, and also much of the polling on the TCJA, is limited. Many of these polls have asked respondents only whether they are “for or against” a given measure. Polls also often ask whether taxes are an important issue as compared to other headline news, and they occasionally ask what people want from tax reform. But researchers rarely ask how people understand the function of taxes within the larger economy or taxes as drivers of economic forces. Polls also tend to separate concern about taxation from concern about the economy (or about education, social security, and similar issues), suggesting that these are all separate issues, when they are in reality quite related. For policy experts, who want to learn how the public understands and reacts to their proposals, these are real polling gaps.

The 2018 VOTER Survey data help move past some of these shortcomings.

The 2018 VOTER Survey, part of a series of opinion polls surveying the same group of approximately 6,000 respondents up to twice annually, asked 16 questions about taxes along several different dimensions. Among a variety of aims, the survey sought to answer nuanced questions such as: What do voters want from tax reform, regardless of their feelings about the 2017 law? How do they understand taxes as a part of larger economic forces? What do they think the 2017 law will accomplish, and for whom?

The survey design allows us to segment voters in a number of different ways. This report, which aims to illuminate current voter views on taxation generally, with a focus on both partisan and intra-partisan divides, examines voter opinions within and across the following categories:

These separate categories overlap (e.g., Cruz primary voters are also highly likely to be Trump general election voters), but looking at them comparatively allows us to see important patterns across different kinds of voters.

For example, the Kasich voters, at 13 percent of the entire Republican primary voter universe surveyed, are regularly at odds with the rest of the Republican voter base on taxation. Obama-Trump voters are also, at 9 percent, a small percentage of all Republicans — but they, too, hold very different views of taxes than standard Romney-Trump supporters. These groups are not large, but they matter for several reasons. First, in our closely divided electorate, policy leaders may need these small, outlier groups to gain majority support. Second, both Kasich voters and Obama-Trump voters, as types, demonstrate that the Republican electorate as a whole is splintered even on core conservative issues like taxation.

Other segmentation methods, including the cluster analysis used by Emily Ekins of the Cato Institute to develop five Trump voter types, also show wide issues splits among Republicans. Ekins suggests that between 30 and 40 percent of the Republican’s views on taxation differ from the party's majority. (x)

At the most general level, the 2018 VOTER Survey data show partisan support for TCJA consistent with the findings of many other polls conducted both before and after the law’s passage.(5)

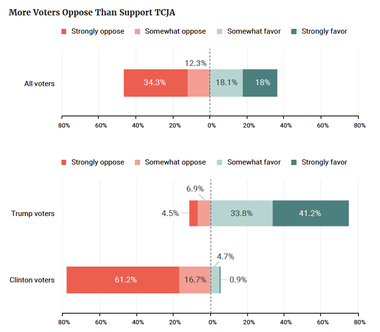

In response to the question “Do you favor or oppose the tax plan that was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Trump?” the public generally is opposed, 46 percent to 36 percent. Intense opposition outweighed intense support almost two to one (Figure 1).

Responses were predictably partisan. Seventy-eight percent of Clinton voters “somewhat” or “strongly oppose” the law, while 75 percent of Trump voters “somewhat” or “strongly favor” it. Again, intense opposition outweighed intense support, with 61 percent of Clinton voters strongly opposing, and 41 percent of Trump voters strongly in favor.

(5) See Bowman, O'Neil, and Sims. Additionally, as just one example of the partisan divide, Gallup showed that 8 percent of Democrats, 76 percent of Republicans, and 34 percent of independents approved of the law as of September 2018. See Megan Brenan, “More Still Disapprove Than Approve of 2017 Tax Cuts,” Gallup News, Gallup, October 10, 2018. Available at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/243611/disapprove-approve-%202017-tax-cuts.aspx.

Figure 1

Americans have historically agreed that they want tax reform in the abstract, but they have disagreed on many specifics. Today, those disagreements may be narrowing.

VOTER Survey data reveal that despite partisan division on the 2017 law itself, Americans are quite aligned on a broad range of tax goals. They want tax changes that stimulate the economy; reduce, rather than increase, federal deficits; and lower both middle-class taxes and taxes on the poor (Figure 2). The majority of voters do not prioritize lowering taxes on corporations, and an even larger percentage do not prioritize lowering taxes on the wealthy.

1A. WHAT VOTERS WANT

Figure 2

Across the spectrum, voters agreed that taxes should drive economic growth. More than 90 percent of all voters — including both Clinton and Trump voters — said that the goal of economic growth is “very important” or “somewhat important.” Voters varied in intensity on this question, with 85 percent of Trump voters, as compared to 57 percent of Clinton voters, rating economic growth as “very important.”

Voters also generally wanted to reduce the federal deficit, with 88 percent of all respondents rating that goal as “very important” or “somewhat important.” However, as with the economic growth question, intensity on the importance of deficits varied. Sixty-six percent of Trump voters, as compared to 36 percent of Clinton voters, said that deficit reduction is “very important.”

Voters also agreed on the importance of lowering middle-class taxes. Ninety-six percent of Trump voters and 90 percent of Clinton voters said that middle-class tax cuts are “somewhat important” or “very important.” The 90 percent or above number held for all four 2016 general election voter types — Obama-Clinton, Romney-Clinton, Obama-Trump, and Romney-Trump. It also held across all Republican primary voters, as well as Clinton primary voters (91 percent) and Sanders primary voters are similar (88 percent).

Eighty-four percent of all voters also agree that lowering taxes for the poor is “somewhat important ” or “very important.” This issue reveals some partisan differences, with 91 percent of Clinton voters as compared to 74 percent of Trump voters answering “somewhat” or “very important.”

1B. WHAT VOTERS DO NOT WANT

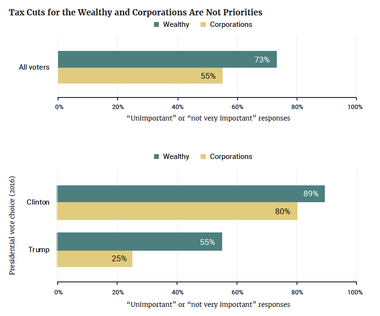

Figure 3

Voters are also clear that they do not prioritize lowering taxes for the wealthy or corporations, two of the centerpiece goals of the TCJA (Figure 3).(6)

(6) This is consistent with other polling conducted before the law’s passage. See, for example, Aaron Lorenzo, “Corporate tax cut unpopular with voters, poll shows," Politico, September 6, 2017. Available at: https://www.politico.com/story/2017/09/06/poll-corporate-tax-cut-is-it-popular-242369; which shows that six in 10 voters believe that corporations pay too little in taxes, and that only 34 percent respondents favored a cut in the corporate rate; See also Hannah Fingerhut, “More Americans favor raising than lowering tax rates on corporations, high household incomes,” FactTank, Pew Research Center, September 27, 2017. Available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/facttank/2017/09/27/more-americans-favor-raising-than-lowering-tax-rates-on-corporations-highhousehold-incomes/.

CUTS FOR THE WEALTHY, CUTS FOR CORPORATIONS

Tax cuts for the wealthy are unpopular. Seventy-three percent of voters say cuts for the wealthy are “unimportant” or “not very important.” Only 10 percent of all VOTER Survey respondents said that tax cuts for the wealthy are “very important,” and only 16 percent said they were “somewhat important.” Not surprisingly, Clinton voters are unified in their opposition to tax cuts for the rich — but a majority of Trump voters are also opposed.

Cutting the corporate rate is also not a priority for voters; a majority is opposed. But views on corporate cuts are more complicated than views on cuts for the wealthy. Fifty-five percent of all voters said that lowering taxes on corporations is either “not very important” or “unimportant,” as compared to 45 percent who said that corporate cuts are “very important” or “somewhat important.” Again, we saw a significant difference in intensity, with nearly twice as many respondents (31 percent) saying that corporate cuts are “unimportant” as those who said they are “very important” (18 percent).

The corporate rate cut elicits significant partisanship — more so than do cuts for the wealthy or other tax goals. Eighty percent of Clinton voters rated corporate cuts as “unimportant” or “not very important,” where 75 percent of Trump voters said corporate cuts are “very important” or “somewhat important.”

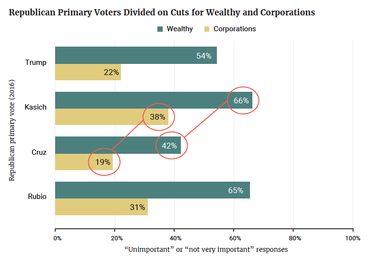

Figure 4

Looking more closely, Republican voters are divided on both cutting taxes for the wealthy and for corporations. On the wealthy, Republican primary voters’ answers ranged by almost 25 percentage points. Forty-two percent of Cruz primary supporters, 54 percent of Trump primary supporters, 65 percent of Rubio supporters, and 66 percent of Kasich supporters said that upper-income cuts are “unimportant” or “not very important” (Figure 4). The biggest gulf is between vote switchers and loyal Republicans. Eighty-seven percent of Obama-Trump voters, as compared to 50 percent of Romney-Trump voters, said that cuts for the wealthy are “unimportant” or “not very important” — a divide of almost 40 percentage points.

On cuts for corporations, Republican primary voters also showed real divides. Nineteen percent of Cruz primary voters said corporate cuts as “unimportant” or “somewhat unimportant,” as compared to 22 percent of Trump primary voters, 31 percent of Rubio primary voters, and 38 percent of Kasich primary voters (Figure 4). Again, on corporate rate cuts, the vote switchers show even more division. Eighty percent of Romney-Trump voters, but only 43 percent of Obama-Trump voters, favored corporate cuts — a 37-percentage-point difference.

The 2018 VOTER Survey asked a few questions that are rarely polled, on how voters think tax reform affects the workings of the economy. Most opinion experts agree that it is difficult to gauge the public’s view of tax reform and economic health, in all likelihood because most people do not feel they have deep understanding of economic mechanisms. That said, VOTER Survey data suggests significant divides on these economic issues.

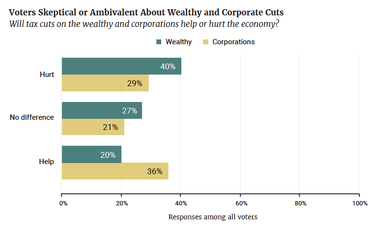

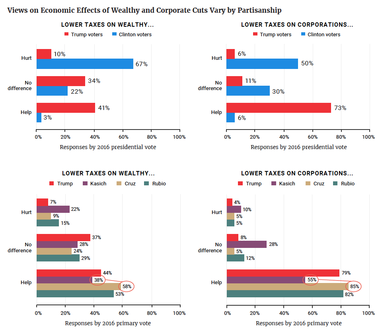

Figure 5

In response to the question, “The tax plan that recently passed lowers taxes on the wealthiest Americans. Do you think this will help the economy, hurt the economy, or not make much difference?” the majority of voters were either skeptical or ambivalent. Only 20 percent of all voters surveyed said that tax cuts for wealthy Americans will “help” the economy, where 40 percent said that they will “hurt” the economy, and 27 percent said they will “not make much difference” (Figure 5).

In response to the question, “The tax plan that recently passed lowers taxes on corporations. Do you think this will help the economy, hurt the economy, or not make much difference?” the split among voters went the other way, slightly favoring “help.” Thirty-six percent said that corporate cuts would “help” the economy, 29 percent said “hurt” the economy, and 21 percent said that corporate cuts would “not make much of a difference” (Figure 5).(7)

Again, both questions yield partisan answers. Virtually no Clinton voters believe that either cuts for the wealthy (10 percent) or cuts for corporations (6 percent) would help the economy. Trump voters are unsure about cuts for the wealthy, with 41 percent saying that such cuts would “help,” 10 percent answering “hurt,” and 34 percent answering “not make much difference” (Figure 6). Trump voters were much more clear about corporate cuts; 73 percent said that they would be good for the economy.

(7) Interestingly, given that this is a question that asks about economic causation, a robust proportion of voters (87 percent) had an answer.

Figure 6

Republican primary voters differed considerably on the question of whether cuts for the wealthy would be good for the economy. Fifty-eight percent of Cruz voters, but only 38 percent of Kasich voters, said that cuts for the wealthy would benefit the economy (Figure 6).

This question also elicited very different responses from Romney-Trump voters, 47 percent of whom said tax cuts for the wealthy are economically beneficial, as compared to only 7 percent of Obama-Trump voters who said the same.

On corporate cuts and economic health, Republican primary voters were even more split. Eighty-five percent of Cruz voters, 79 percent of Trump voters, 82 percent of Rubio voters, but only 55 percent of Kasich voters said that corporate cuts are economically beneficial (Figure 6). Similarly, 38 percent of Obama-Trump voters, as compared to 80 percent of Romney-Trump voters, said corporate tax cuts will “help” the economy.

These answers on tax cuts and overall economic health suggest a few things at the intersection of tax politics, tax policies, and the economy. First, and as a general matter, voters may have theories, however nascent, about taxes as economic incentives, with a particular disdain for the idea that cutting taxes for the wealthy is smart economic policy, though on this question in particular more research is warranted.(8)

Corporate tax cuts are far from popular, but they pull different voters in different directions. Voters as a whole lean slightly toward the belief that corporate tax cuts will “help” (36 percent) the economy rather than “hurt” it (29 percent). However, large numbers also say that corporate cuts either “will not make much difference” to the economy or that they “don’t know.” As Republican leaders regularly promote corporate tax cuts as an economic boon designed to promote growth, voters’ ambivalence here is notable.(9)

Voters are more clearly opposed to tax cuts for the wealthy and do not believe they are good for the economy. A plurality of voters (40 percent) do not believe that tax cuts for the wealthy will yield overall economic prosperity, and more voters believe that tax cuts for the wealthy “will not make much difference” than believe it will "help" the economy.

(8) This is also reflected in Stanley Greenberg’s April 2018 findings. Greenberg argues that linking tax cuts to declining investments in things that would improve the economy — schools, infrastructure, health care — is a powerful public motivator. See Stanley Greenberg and Randi Weingarten, “The Democratic opportunity on the economy and tax cuts,” Memo, Democracy Corps, April 11, 2018. Available at: http://www.democracycorps.com/attachments/article/1081/Dcor_AFT_April%20Tax%20Poll_Memo_4.11.2018_for%20web.pdf.

(9) For example, in December 2017 Donald Trump said “Our plan also lowers the tax on American business from 35 percent all the way down to 21 percent. That’s probably the biggest factor in this plan. We’ve become competitive all over the world. Our companies won’t be leaving our country any longer because our tax burden is so high.” See Jacob Pramuk, “Trump: Slashing taxes on corporations is ‘probably the biggest factor’ in G.O.P. tax plan,” CNBC, December 20, 2017. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2017/12/20/trump-says-corporate-tax-cut-is-biggest-factor-in-gop-tax-plan.html.

Voters, as we have seen, know what they prioritize in tax reform. They do want, personally, to be better off. Beyond that, they have clear priorities: economic growth, deficit reduction, and lower taxes for the middle class. But they are skeptical, at best, that the TCJA will deliver on the kind of change they want.

On the question closest to home — whether the new law would leave “you and your family better off” — voters were not sanguine. Only 24 percent of all respondents thought the new law would leave them “better off,” in stark contrast to the 86 percent who said that lowering taxes for “me and my family” was “very” or “somewhat important.”(10) Answers to the personal benefit question also reflected partisanship, with 49 percent of Trump voters and only 6 percent of Clinton voters reporting that they believed they would see lower taxes as a result of the law.

(10) Note that 19 percent of respondents said they weren’t sure about the law’s effects on their own taxes. This is a relatively large percentage, especially for a concrete, empirical question. Compare this response, for example, to the 12 percent who said they didn’t know whether corporate tax cuts would be good for the economy.

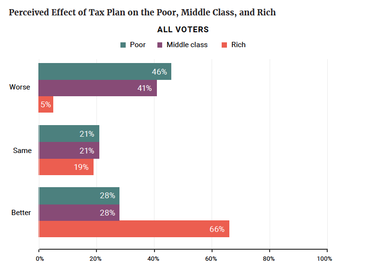

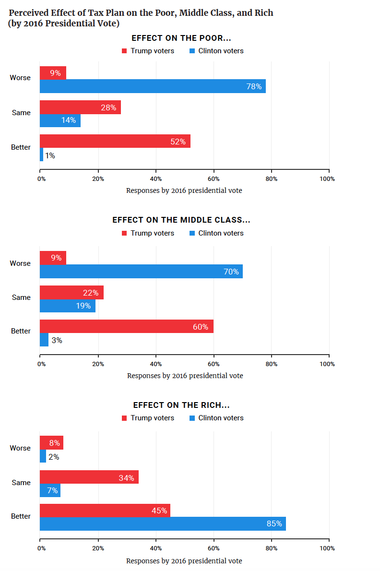

Figure 7

Recall that most voters wanted to see the middle class and also the poor benefit from tax reform, with far fewer prioritizing tax cuts for the wealthy. Voters show little confidence that the law would deliver on these issues. Only 28 percent of respondents thought the law would benefit either the poor or the middle class, while 66 percent thought that the rich would be “better off” (Figure 7).

Figure 8

The same partisanship we have seen in other answers is on display here. Only 3 percent of Clinton voters vs. 60 percent of Trump voters thought the middle class would benefit (Figure 8). Just 1 percent of Clinton voters vs. 52 percent of Trump voters thought the poor would benefit. And 85 percent of Clinton voters vs. 45 percent of Trump voters thought the rich would benefit.

As with other questions, both Kasich primary voters and Obama-Trump voters are skeptical about the tax law’s benefits.

Kasich voters are approximately 20 to 25 percentage points lower than Trump, Cruz, or Rubio voters in predicting benefit for the middle class and 25 to 40 percentage points lower in predicting benefit for the poor.

Obama-Trump voters are 29 percentage points lower than Romney-Trump voters in predicting benefit for the middle class, and they are 24 percentage points less likely to predict benefit for the poor. While most voters believe the rich will benefit from the law, those numbers are more pronounced for Kasich voters by approximately 15 percentage points.

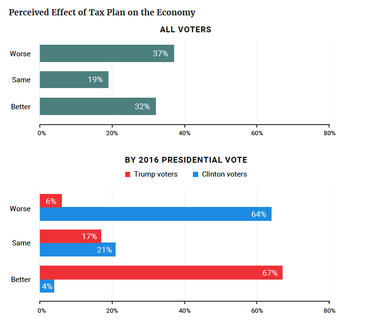

And finally, on the rarely asked question about how the law would affect the larger economy, voters overall were skeptical, with only 32 percent predicting improvement (Figure 9). The same partisanship numbers (4 percent of Clinton voters vs. 67 percent of Trump voters) and splits within the Republican electorate are evident here (Kasich voters and Obama-Trump voters are again the outliers).

Figure 9

The findings of the 2018 VOTER Survey reveal a striking disconnect between what American voters say they want from tax reform, what the 2017 tax law actually prioritizes, and voters’ opinions of and hopes for the impacts of the law itself. Partisanship does color many of the answers, but beyond that, splits among Republican voters are noteworthy, especially on the critical policy questions of corporate tax cuts, tax cuts for the rich, and benefit for the middle class and the economy as a whole.

The survey results should give tax-cutters pause.(11) Politicians today are trying to run on a tax-cutting agenda, but this old orthodoxy seems to be getting less traction with voters — and a new hesitancy is taking shape in real time. Republicans’ campaigns in 2018 clearly show that tax reduction, or at least the TCJA, is not politically appealing.(12) That said, the Republican House leadership is moving forward with a second round of tax cutting focused primarily on making individual rate cuts permanent. If this second round attempts to cast greater benefits for the wealthy than for the middle class in stone (even as proponents maintain that the goal is more take-home pay for working people) it will go directly against what voters have said they want. The proposal again makes clear that the political classes are squarely at odds with the voting public.

The politics of taxation have been shifting for decades, but the 2017 law may prove to be an important pivot.

(11) We leave aside the policy findings suggesting that, at least in the near term, the 2017 TCJA’s centerpiece move, cutting corporate taxes, has led to stock repurchases rather than higher wages, repatriation of tax monies stashed overseas, or investment in infrastructure or research and development. This is an argument that fellows of the Roosevelt Institute have made repeatedly. But for the purposes of this report, we can take seriously the argument that we need to wait longer to see the investment benefits of the tax law, as articulated by the Tax Foundation, among others. See Nicholas Anderson and Nicole Kaeding, “Stock Buybacks Don’t Hinder Investment Spending,” Tax Foundation, June 19, 2018. Available at: https://taxfoundation.org/stock-buybacks-dont-hinderinvestment-spending/.

(12) This is one of Vanessa Williamson’s central arguments: “It is deeply implausible that voters will behave differently due to the very small changes the TCJA made in their individual take-home pay. The legislation is also poorly situated to mobilize Republican voters, whose support for the legislation was lukewarm. The short-term stimulative effects of the TCJA are also unlikely to matter much, both because the effects are small and because the economy matters less for midterm election results. In the longer term, however, Republicans will likely benefit from the law’s upward redistribution targeted to their donor class.” (See Williamson, “The ‘Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’ and the 2018 midterms.”)

Despite a brief uptick in public opinion soon after the law’s passage, this historically unpopular tax law remains under water.(13) The 2018 VOTER Survey data make clear just how much the 2017 law diverges with Americans’ views of how tax reform should work. The majority of voters do not believe that the law will yield benefits for themselves, the middle class, the poor, or the economy as a whole.

Moreover, the data reveal that Trump’s own voters are divided on taxation.(14) A significant percentage of all Trump voters — and greater percentages of some subsets of Trump voters, including Obama-Trump voters and Kasich primary voters — do not believe they will benefit from the law. Many are skeptical that the law meets the goals of tax reform as they envision them. And many do not think that cutting corporate taxes or taxes on the wealthy will be good for the economy.

(13) The RealClearPolitics (RCP) average of polls between April and August 2018 shows disapproval of the law at 42.9 percent and approval at 36 percent. See “Trump, Republicans' Tax Reform Law,” Poll, RealClearPolitics. Available at: https://www.realclearpolitics.com/epolls/other/trump_republicans_tax_reform_law-6446.html.

(14) This is consistent with Emily Ekins' findings that two groups of Trump voters, whom she called the “American Preservationists” and the “Anti-Elites,” favor raising taxes on the wealthy. The divide between these Trump voters and other Trump voters (the “Free Marketeers” and the “Staunch Traditionalists”) is extreme. (See Ekins).

This does not bode well for Republican strategists striving to find ways to keep the 2016 Trump coalition together. Focusing on a strong economy buoyed by presidential leadership on taxation, which is appears to be what Trump continues to want to promote about his own leadership, is not likely to effectively build bonds across the range of Trump supporters.(15)

Democratic voters, including the small but electorally important slice of Romney-Clinton voters, are unified in their disbelief that the TCJA will bring benefits — for themselves, for the poor and middle-class, and for the economy. This creates an interesting calculus for those who want to develop political support for more progressive policies — both more taxation as a disincentive for economically unsound behavior, and also more tax revenue to support publicly funded goods like health insurance, education, infrastructure, and public transportation. Democrats are unlikely to lose support by proposing “repeal” of the Trump law, and they may also be able to propose “replacements” that raise taxes.

This is not to suggest that politicians should run for office with higher taxation, in itself, as a central policy goal. For at least the last decade, voters have ranked as significantly more important other issues, including the economy generally, health care, unemployment/jobs, and “dissatisfaction with government” (described as poor leadership, dissatisfaction with Congress, and corruption).(16) But although the wisdom of running on taxes per se is debatable, the public’s evolving beliefs on taxation may give policymakers more room to develop new combinations of revenue-raising, publicly funded programs, and tax policies designed as economic incentives. The 2017 law, perhaps due to overreach, may prove to be a turning point in public opinion as well as policy development.

(15) Internal Republican polling from September 2018, as reported by Bloomberg News shows that tax cuts did not poll well with Republicans and independents. See Joshua Green, “Internal RNC Poll: Complacent Trump Voters May Cost G.O.P. Control of Congress,” Bloomberg Businessweek, September 18, 2018. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-09-18/internal-rnc-poll-complacent-trump-voters-may-cost-gop-control-of-congress.

(16) Note again that separation of taxes from other economic issues is itself is a strange polling formulation, given the argument that both parties make about the relationship of taxation to these very issues — health care, employment, and the robustness of government itself.

Subscribe to our mailing list for updates on new reports, survey data releases, and other upcoming events.